Here, I want to unpack the choice to place consciousness at the center of our model--there are, of course, many elements to our model, but this extended discussion of consciousness and kairos may help viewers better undersatnd the model on the whole.

To begin our schema for Kinneavy’s model of kairos, Mandy

and I first imagined the concept as having a series of layers that converge to

a point—if we are to imagine kairos as such, what would be at the center. From this question, we branched out our schema.

We had three possibilities based on three excerpts or

implicit allusions in the article. We

first began with the possibility of “a response, a text, or action” as being at

the center of kairos. When focusing on

the first principle of kairos, this makes sense: “the right or opportune time to do something” (Kinneavy 80; emphasis

mine). As the principle states, the kairos serves the action—hence the doing of something. But as Mandy and I discussed further, we

realized that while kairos can provide something to an action, Kinneavy is

conceptualizing kairos more broadly—specifically, the bulk of his discussion is

centered on understanding this second principle: “right measure in doing

something” (80), but while the doing

something is still mentioned in this second principle, Kinneavy spends much

of his time understanding and unpacking the idea of right measure and

propriety.

Mandy and I also became particularly interested in

Kinneavy’s Epistemological dimension of kairos—in particular, the idea that there

is a direct connection between kairos and the construction of knowledge. In

reference to Tillich’s discussion of kairos, Kinneavy explains,

[Tillich] argues for the importance of the kairos approach because it brings theory into practice, it asserts the continuing necessity of free decision, it insists on the value and the norm aspects of ideas, it champions a vital and concerned interest in knowledge because knowledge always is relevant to the situational context, and it provides a better solution to the problem of uniting idea and historical reality. (90; emphasis mine)

In other words, the idea of information is similar to

knowledge in that both terms, to some degree, relate to data, but what I

believe makes the difference between these two words is that knowledge is

social, contextual, situated, and necessarily learned, but information is

amassed and un-interpreted. Kairos,

then, would play a major role in knowledge: it provides a relevance and context

that Tillich is alluding to.

But then, as much as this idea is compelling, Kinneavy is talking about knowledge and kairos,

but he is also uniting knowledge with

the response, text, action. He

provides us with an example from a student that seems to bridge these two

concepts. In his freshman composition

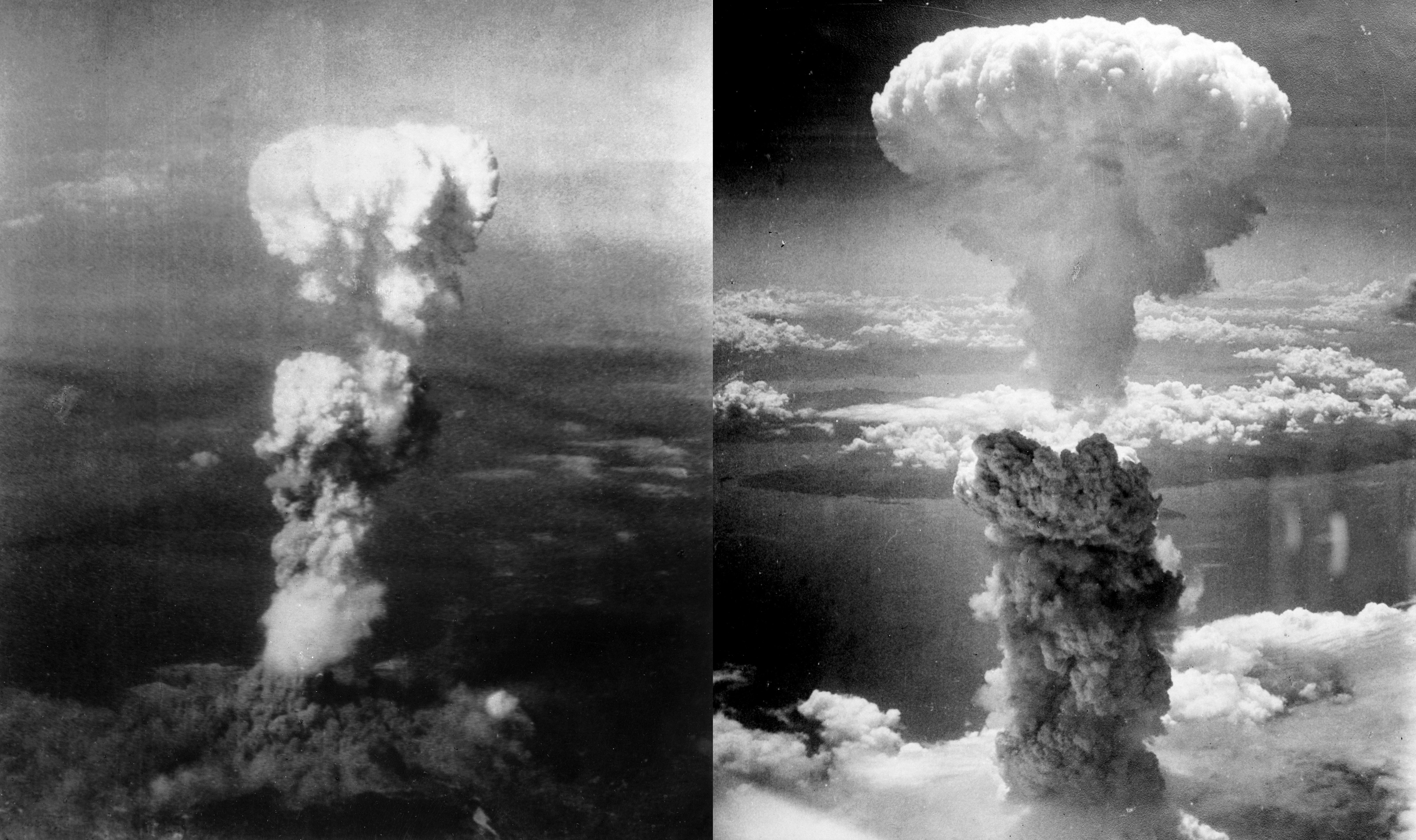

class, he had students read “the Perils of Nuclear Freeze” by Lt. Colonel

Donald Gilleland—Gilleland, here, posits that the US would not be the first to

strike Russia with a nuclear attack. But in conference, a student explained to

him that she was not aware that the

US was the only nation to have ever dropped a nuclear bomb (atomic bomb,

specifically). As Kinneavy writes, “This student obviously did not have the

historical consciousness to write the

topic” (99; emphasis mine). Similar Tillich, Kinneavy sees kairos as bringing

theory to practice, but in this scenario, we’re not only talking about big,

capital “T” Theory, but consciousness or

awareness of factors that contribute

to someone’s worldview. This student, for example, would not have been able to

measure the occasion to successfully write her text because she did not have

the right fluency or networked knowledge or (as Mandy and I

explain) consciousness that would

provide her with help in writing the “right” response. Or a partially “right”

response.

Put another way, consciousness allows us to see kairos as being necessarily networked: in order to know the appropriate response, we have to know if our response fits within our constructed understanding of the situation which has been networked with several materials, concepts, experiences, etc. If we do not have a fuller network or we do not use relevant/appropriate materials to construct the situation (consciousness), we will not be successful. Relatedly, Sheridan shows us that kairos can be a network of nine elements, but is it only just nine? What about history that Kinneavy finds important?

So, as our schema indicates, consciousness is a network of

elements that provides us with the right kinds of knowledge to know what is

relevant, what is appropriate, and what are the “critical moments” that are important

within historical context to present.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.